Renowned psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton on the Goldwater Rule: We have a duty to warn if someone may be dangerous to others.

23 april, 2020

There will not be a book published this fall more urgent, important, or controversial than The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump, the work of 27 psychiatrists, psychologists and mental health experts to assess President Trump’s mental health. They had come together last March at a conference at Yale University to wrestle with two questions. One was on countless minds across the country: “What’s wrong with him?” The second was directed to their own code of ethics: “Does Professional Responsibility Include a Duty to Warn” if they conclude the president to be dangerously unfit?

Originally published at billmoyers.com, September 14, 2017

As mental health professionals, these men and women respect the long-standing “Goldwater rule” which inhibits them from diagnosing public figures whom they have not personally examined. At the same time, as explained by Dr. Bandy X Lee, who teaches law and psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine, the rule does not have a countervailing rule that directs what to do when the risk of harm from remaining silent outweighs the damage that could result from speaking about a public figure — “which in this case, could even be the greatest possible harm.”

It is an old and difficult moral issue that requires a great exertion of conscience. Their decision: “We respect the rule, we deem it subordinate to the single most important principle that guides our professional conduct: that we hold our responsibility to human life and well-being as paramount.”

Hence, this profound, illuminating and discomforting book undertaken as “a duty to warn.”

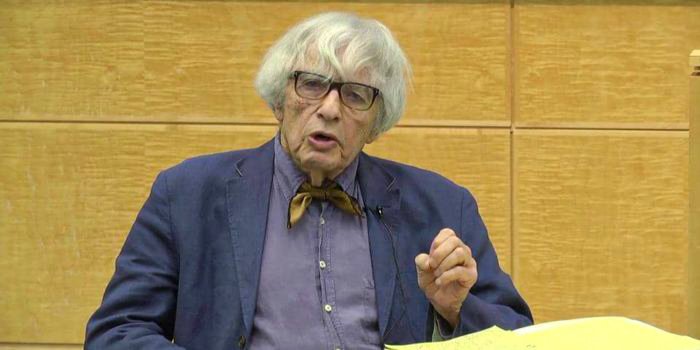

The foreword is by one of America’s leading psychohistorians, Robert Jay Lifton. He is renowned for his studies of people under stress — for books such as Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima (1967), Home from the War: Vietnam Veterans — Neither Victims nor Executioners (1973), and The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide (1986). The Nazi Doctors was the first in-depth study of how medical professionals rationalized their participation in the Holocaust, from the early stages of the Hitler’s euthanasia project to extermination camps.

The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump will be published Oct. 3 by St. Martin’s Press.

Here is my interview with Robert Jay Lifton — Bill Moyers

Bill Moyers: This book is a withering exploration of Donald Trump’s mental state. Aren’t you and the 26 other mental health experts who contribute to it in effect violating the Goldwater Rule? Section 7.3 of the American Psychiatrist Association’s code of ethics flatly says: “It is unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion [on a public figure] unless he or she has conducted an examination and has been granted proper authorization.” Are you putting your profession’s reputation at risk?

Robert Jay Lifton: I don’t think so. I think the Goldwater Rule is a little ambiguous. We adhere to that portion of the Goldwater Rule that says we don’t see ourselves as making a definitive diagnosis in a formal way and we don’t believe that should be done, except by hands-on interviewing and studying of a person. But we take issue with the idea that therefore we can say nothing about Trump or any other public figure. We have a perfect right to offer our opinion, and that’s where “duty to warn” comes in.

Moyers: Duty to warn?

Lifton: We have a duty to warn on an individual basis if we are treating someone who may be dangerous to herself or to others — a duty to warn people who are in danger from that person. We feel it’s our duty to warn the country about the danger of this president. If we think we have learned something about Donald Trump and his psychology that is dangerous to the country, yes, we have an obligation to say so. That’s why Judith Herman and I wrote our letter to The New York Times. We argue that Trump’s difficult relationship to reality and his inability to respond in an evenhanded way to a crisis renders him unfit to be president, and we asked our elected representative to take steps to remove him from the presidency.

Moyers: Yet some people argue that our political system sets no intellectual or cognitive standards for being president, and therefore, the ordinary norms of your practice as a psychiatrist should stop at the door to the Oval Office.

Lifton: Well, there are people who believe that there should be a standard psychiatric examination for every presidential candidate and for every president. But these are difficult issues because they can’t ever be entirely psychiatric. They’re inevitably political as well. I personally believe that ultimately ridding the country of a dangerous president or one who’s unfit is ultimately a political matter, but that psychological professionals can contribute in valuable ways to that decision.

Moyers: Do you recall that there was a comprehensive study of all 37 presidents up to 1974? Half of them reportedly had a diagnosable mental illness, including depression, anxiety and bipolar disorder. It’s not normal people who always make it to the White House.

Lifton: Yes, that’s amazing, and I’m sure it’s more or less true. So people with what we call mental illness can indeed serve well, and people who have no discernible mental illness — and that may be true of Trump — may not be able to serve, may be quite unfit. So it isn’t always the question of a psychiatric diagnosis. It’s really a question of what psychological and other traits render one unfit or dangerous.

Moyers: You write in the foreword of the book: “Because Trump is president and operates within the broad contours and interactions of the presidency, there is a tendency to view what he does as simply part of our democratic process, that is, as politically and even ethically normal.”

Lifton: Yes. And that’s what I call malignant normality. What we put forward as self-evident and normal may be deeply dangerous and destructive. I came to that idea in my work on the psychology of Nazi doctors — and I’m not equating anybody with Nazi doctors, but it’s the principle that prevails — and also with American psychologists who became architects of CIA torture during the Iraq War era. These are forms of malignant normality.

For example, Donald Trump lies repeatedly. We may come to see a president as a liar as normal. He also makes bombastic statements about nuclear weapons, for instance, which can then be seen as somehow normal. In other words, his behavior as president, with all those who defend his behavior in the administration, becomes a norm.

We have to contest

Moyers: Witnessing professionals? Where did this notion come from?

Lifton: I first came to it in terms of psychiatrists assigned to Vietnam, way back then. If a soldier became anxious and enraged about the immorality of the Vietnam War, he might be sent to a psychiatrist who would be expected to help him be strong enough to return to committing atrocities.

So there was something wrong with what professionals were doing, and some of us had to try to expose this as the wrong and manipulative use of our profession. We had to see ourselves as witnessing professionals.

And then of course, with the Nazi

So that’s another malignant normality. Professionals were reduced to being automatic servants of the existing regime as opposed to people with special knowledge balanced by a moral baseline as well as the scientific information to make judgments.

Moyers: And that should apply to journalists, lawyers, doctors —

Lifton: Absolutely. One bears witness by taking in the situation — in this case, its malignant nature — and then telling one’s story about it, in this case with the help of professional knowledge, so that we add perspective on what’s wrong, rather than being servants of the powers responsible for the malignant normality. We must be people with a conscience in a very fundamental way.

Moyers: And this is what troubled you and many of your colleagues about the psychologists who helped implement the US policy of torture after 9/11.

Lifton: Absolutely. And I call that a scandal within a scandal, because yes, it was indeed professionals who became architects of torture, and their professional society, the American Psychological Association, which encouraged and protected them until finally protest from within that society by other members forced a change. So that was a dreadful moment in the history of psychology and in the history of professionals in this country.

Moyers: Some of the descriptions used to describe Trump — narcissistic personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, paranoid personality disorder, delusional disorder, malignant narcissist — even some have suggested early forms of dementia — are difficult for

Lifton: I think that’s very accurate. I agree that there’s an all-enveloping destructiveness in his character and in his psychological tendencies. But I’ve focused on what professionally I call solipsistic reality. Solipsistic reality means that the only reality he’s capable of embracing has to do with his own self and the perception by and protection of his own self. And for a president to be so bound in this isolated solipsistic reality could not be more dangerous for the country and for the world.

In that sense, he does what psychotics do. Psychotics engage in, or frequently engage in a view of reality based only on the self. He’s not psychotic, but I think ultimately this solipsistic reality will be the source of his removal from the presidency.

Moyers: What’s your take on how he makes increasingly bizarre statements that are contradicted by irrefutable evidence to the contrary, and yet he just keeps on making them? I know some people in your field call this a delusional disorder, a profound loss of contact with external reality.

Lifton: He doesn’t have clear contact with reality, though I’m not sure it qualifies as a bona fide delusion. He needs things to be a certain way even though they aren’t, and that’s one reason he lies. There can also be a conscious manipulative element to it.

When he put forward, and politically thrived on, the falsehood of President Obama’s birth in Kenya, outside the United States, he was manipulating that lie as well as undoubtedly believing it in part, at least in a segment of his personality.

In my investigations, I’ve found that people can believe and not believe something at the same time, and in his case, he could be very manipulative and be quite gifted at his manipulations. So I think it’s a combination of those.

Moyers: How can someone believe and not believe at the same time?

Lifton: Well, in one part of himself, Trump can know there’s no evidence that Obama was born in any place but Hawaii in the United States. But in another part of himself, he has the need to reject Obama as a president of the United States by asserting that he was born outside of the country.

He needs to delegitimate Obama. That’s been a strong need of Trump’s. This is a personal, isolated solipsistic need which can coexist with a recognition that there’s no evidence at all to back it up. I learned about this from some of the false confessions I came upon in my work.

Moyers: Where?

Lifton: For instance, when I was studying Chinese communist thought reform, one priest was falsely accused of being a spy, and was under physical duress — really tortured with chains and in other intolerable ways.

As he was tortured and the interrogator kept insisting that he was a spy, he began to imagine himself in the role of a spy, with spy radios in all the houses of his order. In his conversations with other missionaries, he began to think he was revealing military data to the enemy in some way.

These thoughts became real to him because he had to entered into them and convinced the interrogator that he believed them in order to remove the chains and the torture. He told me it seemed like someone creating a novel and the novelist building a story with characters

Something like that could happen to Trump, in which the false beliefs become part of a narrative, all of which is fantasy and very often bound up with conspiracy

Moyers: It’s as if he believes the truth is defined by his words.

Lifton: Yes, that’s right. Trump has a mind that in many ways is always under duress, because he’s always seeking to be accepted, loved. He sees himself as constantly victimized by others and by the society, from which he sees himself as fighting back. So there’s always an intensity to his destructive behavior that could contribute to his false beliefs.

Moyers: Do you remember when he tweeted that President Obama had him wiretapped, despite the fact that the intelligence community couldn’t find any evidence to support his claim? And when he spoke to a CIA gathering, with the television cameras running, he said he was “a thousand percent behind the CIA,” despite the fact that everyone watching had to know he had repeatedly denounced the “incompetence and dishonesty” of that same intelligence community.

Lifton: Yes, that’s an extraordinary situation. And one has to invoke here this notion of a self-determined truth, this inner need for the situation to take shape in the form that the falsehood claims. In a sense this takes precedence over any other criteria for what is true.

Moyers: What other hazardous patterns do you see in his behavior? For example, what do you make of the admiration that he has expressed for brutal dictators — Bashar al-Assad of Syria, the late Saddam Hussein of Iraq, even Kim Jong Un of North Korea — yes, him — and President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, who turned vigilantes loose to kill thousands of drug users, and of course his admiration for Vladimir Putin. In the book Michael Tansey says, “There’s considerable evidence to suggest that absolute tyranny is Donald Trump’s wet dream.”

Lifton: Yes. Well, while Trump doesn’t have any systematic ideology, he does have a narrative, and in that narrative, America was once a great country, it’s been weakened by poor leadership, and only he can make it great again by taking over. And that’s an image of himself as a strongman, a dictator.

It isn’t the clear ideology of being a fascist or some other clear-cut ideological figure. Rather, it’s a narrative of himself as being unique and all-powerful. He believes it, though I’m sure he’s got doubts about it.

But his narrative in a sense calls forth other strongmen, other dictators who run their country in an absolute way and don’t have to bother with legislative division or legal issues.

Moyers: I suspect some elected officials sometimes dream of doing what an unopposed autocrat or strongman is able to do, and that’s demand adulation on the one hand, and on the other hand, eradicate all of your perceived enemies just by turning your thumb down to the crowd. No need to worry about “fake media” — you’ve had them done away with. No protesters. No confounding lawsuits against you. Nothing stands in your way.

Lifton: That’s exactly right. Trump gives the impression that he would like to govern by decree. And of course, who governs by decree but dictators or strongmen? He has that impulse in him and he wants to be a savior, so he says, in his famous phrase, “Only I can fix it!”

That’s a strange and weird statement for anybody to make, but it’s central to Trump’s sense of self and self-presentation. And I think that has a lot to do with his identification with dictators. No matter how many they kill and no matter what else they do, they have this capacity to rule by decree without any interference by legislators or courts.

In the case of Putin, I think Trump does have involvements in Russia that are in some way determinative. I think they’ll be important in his removal from office. I think he’s aware of collusion on his part and his campaigns, some of which have been brought out, a lot more of which will be brought out in the future.

He appears to have had some kind of involvement with the Russians in which they’ve rescued him financially and maybe continue to do

Moyers: I want to ask you about another side of him that is taken up in the book. It involves the much-discussed video that appeared during the campaign last year which had been made a decade or so ago when Trump was newly married. He sees this actress outside his bus and he says, “I better use some Tic Tacs just in case I start kissing her,” and then we hear sounds of Tic Tacs before Trump continues. “You know,” he says, “I’m automatically attracted to beautiful — I just start kissing them. It’s like a magnet, just kiss, I don’t even wait.” And then you can hear him boasting off camera, “When you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything, grab them by the…. You can do anything.”

Lifton: In addition to being a strongman and a dictator, there’s a pervasive sense of entitlement. Whatever he wants, whatever he needs in his own mind, he can have. It’s a kind of American celebrity gone wild, but it’s also a vicious anti-female perspective and a caricature of male macho.

That’s all present in Trump as well as the solipsism that I mentioned earlier, and that’s why when people speak of him as all-pervasive on many different levels of destructiveness, they’re absolutely right.

Moyers: And it seems to extend deeply into his relationship with his own family. There’s a chapter in The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump with the heading, “Trump’s Daddy Issues.” There’s several of his quotes about his daughter, Ivanka. He said, “You know who’s one of the great beauties of the world, according to everybody, and I helped create her? Ivanka. My daughter, Ivanka. She’s 6 feet tall. She’s got the best body.”

Again: “I said that if Ivanka weren’t my daughter, perhaps I’d be dating her.” Ivanka was 22 at the time. To a

When Howard Stern, the radio host, started to say, “By the way, your daughter —” Trump interrupted him with “She’s beautiful.” Stern continued, “Can I say this? A piece of ass.” To which Trump replied, “Yeah.” What’s going on here?

Lifton: In addition to everything else and the extreme narcissism that it represents, it’s a kind of unbridled sense of saying anything on one’s mind as well as an impulse to break down all norms because he is the untouchable celebrity. So just as he is the one man who can fix things for the country, he can have every woman or anything else that he wants, or abuse them in any way he seeks to.

Moyers: You mentioned extreme narcissism. I’m sure you knew Erich Fromm —

Lifton: Yes, I did.

Moyers: — one of the founders of humanistic psychology. He was a Holocaust survivor who had a lifelong obsession with the psychology of evil. And he said that he thought “malignant narcissism” was the most severe pathology — “the root of the most vicious destructiveness and inhumanity.” Do you think malignant narcissism goes a long way to explain Trump?

Lifton: I do think it goes a long way. In early psychoanalytic thought, narcissism was — and still, of course, is — self-love. The early psychoanalysts used to talk of libido directed at the self. That now feels a little quaint, that kind of language. But it does include the most fierce and self-displaying form of one’s individual self.

And in this way, it can be dangerous. When you look at Trump, you can really see someone who’s destructive to any form of life enhancement in virtually every area. And if that’s what Fromm means by malignant narcissism, then it definitely applies.

Moyers: You said earlier that Trump and his administration have brought about a kind of malignant normalcy — that a dangerous president can become normalized. When the Democrats make a deal with him, as they did recently, are they edging him a little closer to being accepted despite this record of bizarre behavior?

Lifton: We are normalizing him when the Democrats make a deal with him. But there’s a profound ethical issue here and it’s not easily answered. If something is good for the country — perhaps the deal that the Democrats are making with Donald Trump is seen or could be understood by most as good for the country, dealing with the debt crisis — is that worth doing even though it normalizes him? If the Democrats do go ahead with this deal, they should take steps to make clear that they’re opposing other aspects of his presidency and of him.

Moyers: There’s a chapter in the book entitled, “He’s Got the World in His Hands and His Finger on the Trigger.” Do you ever imagine him sitting alone in his office, deciding on a potentially catastrophic course of action for the nation? Say, with five minutes to decide whether or not to unleash thermonuclear weapons?

Lifton: I do. And like many, I’m deeply frightened by that possibility. It’s said very often that, OK, there are people around him who can contain him and restrain him. I’m not so sure they always can or would. In any case, it’s not unlikely that he could seek t